An Illustrated History of Chess

Contents:

1 Origins

2 Early Chess

3 Thailand, Burma

4 China

5 From China?

6 Korea

7 Japan

8 Evolution

9 Europe

10 Variants

Exotic Chess

Products

The History

of Chess

How

To Play

Chess from

Around the World

An Illustrated History of Chess_________________8____

Taking

another step back in time, let's look at how our modern chess

evolved out of the ancient Persian game. At

the right is a conventional carving of an ancient Indian king,

in his glory, riding on an elephant back rig (that's called a

howdah). |

ancient sculpted king on an elephant |

If

you abstract that shape — just block out its general form

and round off the edges — you come up with something like

this. What we have here is a typical ancient chess king, as it

was represented all over central Asia, Northern Africa, and as

it came into Europe. You can see the bulk of the elephant's body,

the rising ridge of the howdah, and the blip of the king

himself up above it all. The one shown here was actually found in Scandinavia, dated to the 8th or 9th century. |

ancient abstract king |

ancient european queen, from 12th century Spain |

The Europeans who inherited these shapes frankly did not know what to make of them. Here is an ancient queen, based on that same shape, squatted down into a coloseum, so that she takes the form of the ancient piece. |

But

there was another force at work in the shaping of chessmen. Everywhere that chess went, it met up with craftsmen who wanted to try their lathes on the design the of pieces. The ancient pieces in the Muslim world were eclipsed by various toadstool-like shapes. Pieces in this style are so similar to each other that they are hard to tell apart. You will remember a similar evolution of pieces in the Thai chess set we already looked at (page 3). |

|

an ornate example the "Selenus" style of chessmen. This lean, spindly style enjoyed widespread popularity from the 16th, well into the 18th century, especially in central Europe. |

The

lathe turners of Europe also had their way with the shapes of

chessmen. In the western world, it became fashionable to make

the pieces as lean as possible, tall and spindly, elegant figures. |

| But

at the same time, figurative, representational pieces have been

cropping up all over the world, in all cultural settings. These

conflicting tendancies, toward abstraction on one hand and literal

representation on the other, are largely responsible for the great

variety of forms chessmen have taken over the ages. The most enduring tradition of carved representational figures took place in northern Europe, where sculpted forms like the one shown at the right have been found, spanning a broad area, for several centuries. |

The most famous chess find of all: In 1831, nearly four complete sets of Scandinavian style chessmen were found on the Scottish Isle of Lewis, dating back to the 12th century. |

|

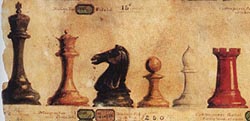

By the

middle of the 18th century, most of central Europe had come to favor

the Régence style of chessmen. This style flourished

for some 150 years as the most popular style of chessmen, well into

the early 20th century. The Régence (or Regency) chessmen have an elegant, yet simple shape. But the figures are a bit too similar to one another for modern taste. The queen, at a glance, can be mistaken for a bishop, and the bishop for a pawn. |

The

chessmen which are considered standard today were originally copyrighted

in 1849, by Nathaniel Cook. Howard Staunton, the famous chess

master and chess author of the mid-late 19th century, allowed

his name to be used for these pieces, and we still know them as

the Staunton style. Seventy-five years later, in 1924, the Staunton

style was officially selected as the standard for international

tournament play, winning out over the popularity of the Régence

style. |

|

|

HOME

PAGE CHESS PRODUCTS: International | Asian | Reproductions | Unique | Rare | Other Games CHESS HISTORY PAGES: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 HOW TO PLAY: Chess | Courier Chess | Sittuyin | Xiangqi | Shogi | Shatranj | Janggi Makruk | Shatar | Dou Shou Qi | Luzhanqi LINKS: Chess Variants | Chess History | Chess Articles | Mah Jongg AFFILIATED SITES: Rick Knowlton | Courier Chess | Knowlton Mosaics Ken Knowlton | Insite Age | VerySpecial.us CONTACT US |